As mankind searches within the wellspring of curiosity, time continues to lapse far into the reaches of the unknown. As we human beings sift through the realm of time, the treasures of the past are carried into the future, buried deep within the bosom of eternity. Our curious minds starve. We thirst for what we were, what we know, and where we are going. We crave the spiritual connection that exists deep within our souls. Our minds are not satisfied or justified unless we have answers to our questions. We desire a clear satisfaction for the truth yet we cloud our innocence with complex puzzles of the mind. It hinders our intimacy with things spiritual. Of those who have found the wellspring, they find the prize and protect it with a gladiator's heart. Wild at heart are those who adventure past the barricades and venture deep into their souls. A romance exists within them once the veil of truth is uncovered. Touching, embracing, loving, ever satisfied. This was Pete Starr: adventurer of the soul, romantic to the truth, and husband to the beautiful Sierra Nevada.

To

shining summits, bright and cool

The

mountain trails from snow are free

The

flashing trout are in the pool.

All

winter long, the lure and spell

Of

glittering lakes and towering trees

Of

rushing streams and pine tree smell

And

flowering meadows haunted me.

Of

all the peace on earth there's none

Like

evening in my camp fire gleam

No

shrine like God's own starlit dome

Nor

wine like waters from my stream.

What

song like sylvan solitude

Stirred

softly by the snow kissed breeze

Or

water ouzel's sweet notes tuned

To

swirling stream's glad melodies

Lure

of Sierra, wild and free

Jewels

deep set in shining skies

Defiant

mountains beckon me

To

glory and dream in their paradise.

-

Walter Pete A. Starr, 1933

I had always placed the utmost respect on the pioneers of mountaineering; true adventurers. For those men and women who have forged beyond the outer reaches of the known: Theodore Solomons, Joseph LeConte, Francis Farquhar, Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn, Bestor Robinson, and, of course, Walter Pete Starr Jr. They were the fathers to an infant climbing community. They loved their beloved Sierra Nevada and the mountains that beckoned them. Future mountaineers would follow in their footsteps and feel the same romantic embrace. Legendary as they were, I had read of their adventures through university digests, memoirs and countless guidebooks. But when I stumbled upon a brief narrative in one of Claude Fiddler's guidebooks regarding Pete Starr's tragic death in the Minarets back in the autumn of 1933, I was drawn to know more about this man and his experiences in the high country. I would find this was a man who dedicated his life to something he held close within his soul and died with it deep in his heart.

After climbing Clyde Minaret the year before, I was fascinated with the haunting beauty of the Minarets. I can only imagine how the early pioneers first felt when they cast their eyes upon the striking turrets and needles. Stretching, seeking, piercing an azure Sierra skyline. Rugged jewels cast upon a captivating landscape. For Pete, it was his first and only love. My quest had begun by finding more information on Pete's death and inquired through summitpost.org with some fellow mountaineers via the information highway. As a member of Summitpost.org, I posted a thread that simply stated Walt Starr's Remains, in order to establish interest. And interest I received. Several responses were posted as to where I could find more about Pete and how he fell to his death upon the NW Face of Michael Minaret. I was told that William Alsup, a federal judge in San Francisco, had published a book called Missing In The Minarets: The Search For Walter A. Starr Jr.' in 2001. Alsup performed extensive research in order to bring light to the mystery of Pete's disappearance and the final discovery of his earthly remains by Norman Clyde in late August 1933. Before publishing the book, he requested the assistance of Yosemite climbing veteran Steve Roper to visit Mr. Starr's gravesite, whose final resting place remains on the NW Face. On a historical note, Pete's father, a prominent mountaineer himself, requested that Jules Eichorn and Norman Clyde inter Pete's body, on the ledge he was found. Roper was sent to that same ledge in 1999 to locate the gravesite, answer a few unsettled questions and pay respects to such a prolific figure of Sierra mountaineering. After digesting the book myself and examining the facts collected by both Alsup and Roper, it left me unsettled. Why did Alsup's book conclude where fact seemed to blend with a degree of fiction? Why did an essence of mystery still linger within the personal accounts of Clyde and Eichorn? Why did Roper's findings draw inconclusive answers? What more could have been to done to honor this man? I was drawn personally and desired to preserve the memory of a man who was the Sierra Nevada. A man who died while seeking out his true love. With the interest and help of other climbers, we committed ourselves as torchbearers and stewards in the preservation of some Sierra Nevada climbing history. We wanted our mountaineering brethren to know about the man who had discovered his soul by living and dying in his beloved Sierra Nevada.

After months of emails and telephone conversations, the project was taking shape. A modest team of mountaineers was assembled who shared the same passion as I did.

Bob Burd (aka The Bataan Death March King'), an engineer from the Bay area,

was our go to man for detailed backcountry knowledge and other juicy tidbits.

Romain Wacziarg, an economics professor from Stanford University, self-appointed

French humorist and well-rounded mountaineer, was our acting liaison with the

Stanford Alumni Association. Starr had been a Stanford alumnus and the SAA was

interested to help us in any way possible. Romain further submitted our

proposal to the SAA, which eventually led to the funding for Pete Starr's

bronze memorial plaque.

Michele Beaty, of Santa Cruz, would be our non-resident paleontologist and the

glue that keep the team from coming apart.

Bob, Michele and myself had climbed together the season prior. This would be the first time the three of us would be teaming up to climb with Romain. I was confident we had the ideal team to pull the project off. We aptly named our project: The Pete Starr Memorial Project' and formulated some objectives. These objectives would encompass the historic preservation of a prolific figure in Sierra Nevada mountaineering, place a memorial plaque near the gravesite, answer a few open ended questions and possibly search for the contents Pete Starr had lost during his fatal fall. Two thirds of a decade had passed and the answers wouldn't come easy. Considering the terrain we'd be on and the limited knowledge we possessed about Michael Minaret including the approach, it would challenge us all. We eventually decided to apply for a grant through the American Alpine Club (www.americanalpineclub.org/) in hopes for financial support. In response, the AAC asked us to apply for a grant and we sent in our proposal. Three months later, we got the exciting news. Not only were we awarded a financial grant from the AAC but received their generous moral and ethical support as well. Even our brothers and sisters of Summitpost.org encouraged us through emails and thread responses. We planned the trip to Michael Minaret during the Labor Day weekend (August 29th Sept 1st). The excitement would build as the summer months passed by. Our trip itinerary was now solid and the project would soon shift into second gear.

With the plaque and a few other necessities, I decided to haul them up to the base of Clyde Minaret a week prior. This I would do with the help of Paul Singer, a good friend from Fresno. On August 22nd, Paul and I drove from Fresno, through Yosemite, and on over to the town of Mammoth. Once there, we headed to the Minaret Lake trailhead near Devil's Postpile. After squaring up the 14 x 24 bronze plaque inside my pack and ensuring we had all that we needed, Paul and I headed up the trail around 8:15 PM. As dusk settled into darkness, I donned my headlamp. The night sky was moonless and the old growth forests along the way were pitch black. The beam of my headlamp was our only true comfort as we tried to spook each other with horror stories along the way. Once at Minaret Lake, I was really beginning to feel the plaque's weight, including the other equipment placed inside my pack. Just the plaque alone weighed 37 lbs. Paul took over at this point and hauled it the remaining distance up to Cecile Lake, near the base of Clyde Minaret. We arrived at the lake around 11:47 PM. Once there, we found a large boulder on the south end of the lake which provided enough space underneath it to cache' the gear and plaque. After covering up the gap with stones and getting a small bite to eat, Paul and I headed back to the trailhead. We had hoped to make it back there by 4:00 AM. But this was not to be! My batteries to the headlamp had drained on the trip up. Without moonlight, we'd be left to our night vision to navigate some 3rd class terrain and the old growth forest above Minaret Falls. We pushed on nonetheless. Fatigue and sleep deprivation were setting in and I was no longer in the mood to stumble the rest of the way home. So we opted to sack out near the north end of Minaret Lake. We didn't have much for insulation other than light outer shells and light hiking pants. With temperatures now dropping into the low 30's, it made for quite the chilly impromptu bivy experience. Paul and I still managed to huddle next to each other and keep warm. By 4:20 AM, the moon finally peeked over the southeastern side of Minaret Lake and we made our way out of there; teeth still chattering. We would make it back to the trailhead by 7:30 AM and finally headed into the town of Mammoth for breakfast. Perry's ended up being our breakfast rendezvous, with a must side trip over to the Looney Bean' for coffee. With food in our bellies and coffee revitalizing our souls, we drove for Fresno. The best was yet to come.

Mt. Starr

Ruby Wall

I received a call from Bob a few days before the trip to see if I wanted to join him for an acclimatization day trip out to Mt. Starr and the Ruby Wall on the 28th. The plan was to hike up to Mt. Starr and then solo the Ruby Wall, a 5th class ridge traverse. Our hopeful goal was to traverse the ridge to Mt. Mills and then head back to the trailhead. Hopefully, we would return no later than 7:00 PM to meet Michele and Romain as they arrived in town. For me, this meant driving from Fresno around 1:00 AM and meet Bob near Mammoth by 5:00 AM. I agreed and planned to bring everything that we needed for the day after. In a blaze of speed, I managed to arrive there at the prescribed time but having left at 2:00 AM from Fresno, an hour later. Needless to say, I avoided a few late night speed traps inside Yosemite National Park. I met Bob near Hwy 203. After we parked Bob's car, we took off in my truck to Rock Creek, south of Mammoth. We drove to the Mosquito Flat trailhead and got a 7:00 AM start. Bob, an established marathon backcountry traveler, wasn't feeling good that day and his paced showed it. I, on the other hand, was glad his pace was down a notch and I stayed closely on his heels. Although some of the terrain was 3rd class, Bob and I made quick work of Mt. Starr. We were on the summit by 8:30 AM, headed through Mono Pass, and over to Ruby Wall's south end.

the beginning of Ruby Wall's south end

Once on the ridge, the terrain stepped

up to 4th class with occasional 5th class moves, tucked

in for good measure. Midway through the ridge traverse, Bob was feeling better

and slowly pulled ahead. We stumbled upon one distinct gendarme

that had my name written all over it and I promptly took to climbing it. After

a few moves of 5.7, I scrambled to its pinnacle

and got a few photo shots. The pinnacle itself overhung at the top of the Ruby

Wall, making for some wild exposure! It was good to get on a solid piece of

granite. The traverse was a typical Sierra ridge traverse, broken by gendarmes

and debris-scattered slabs. A few sections had decomposing granite but for the

most part it was an enjoyable traverse.

After down climbing the gendarme, Bob and I head for Ruby Peak proper. Once we signed the summit register, a decision was made to head down Ruby Peak's East Ridge toward Mills Lake. I had slowed us down a bit and we wouldn't make Mt. Mills in time to meet our scheduled return time. None the less, we were both satisfied we had enjoyed the traverse to this point and agreed we'd be back again to take on its entirety in the future. Once again, Bob picked up the tempo and left me in his wake. The terrain terraced down to Ruby Lake via 3rd class ledges. I paused to admire Ruby Lake's glistening water in the afternoon sun and the huge striking wall of Ruby Wall. After passing Ruby Lake, I finally caught up with Bob on an established trail and we were back at the truck by 6:05 PM.

Once in the truck, we were both feeling the fatigue of the day trip and wanted nothing more than check into our motel in Mammoth and grab a nice hot shower! We arrived in Mammoth around 6:35 PM and grabbed some Starbucks to liven up our spirits. By 7:00 PM, we were checked into the hotel. Michele arrived 15 minutes after we had checked in and we all got situated with the living arrangements. Romain finally showed up and the Minaret Four' were together at last. After a refreshing shower, we prepared to go out and get a good meal in before heading out the next day to Michael Minaret. Bob broke out his Visa (big mistake!) and treated us all to a delightful dinner at Alpinerose, a Swiss cuisine restaurant. Good friends, fine wine, and the ambience of the mountain environment made things complete. We reminisced and swapped stories about our summer exploits. It was a special feeling for all of us to finally kick the project into high gear. Things were finally materializing into reality. We toasted to the occasion and recognized Pete for the accomplishments he had made during his lifetime. We returned to the hotel, sorted the gear, and ditched the things we wouldn't need. After all the gear was staged, we finally settled in for the evening. We knew that the days ahead would require our full attention and no one wanted to sell the trip short.

At 1:00 AM, I woke to the sound of gut wrenching hurls. I eventually figured out that it was Bob, only after spotting his empty bed and the bathroom light turned on. The two others had woken and we all wondered what had Bob's stomach so troubled. For ten straight minutes, Bob continued to vomit until his gag reflex kicked in as he dry heaved for the next five minutes. It sounded fairly painful and we all felt sympathy for him. We wondered how this might affect the outcome of our trip. Bob had already committed to hauling the plaque up Michael Minaret. After humping the plaque to Cecile Lake myself a week ago, there was little chance that I wanted to take it the remaining way. But if worse came to worse, I'd find some way that it would get up there. Bob came out of the bathroom somewhat leveled and wasn't sure if he'd make it the next day. We all finally got back to sleep but not without all of us taking a moment to reflect of what we'd do if Bob couldn't make it the next day.

5:30 AM rolled around and we all prepped for the

day. I asked Bob how he was feeling, only to get a vague response to my

question. I was left with the impression that he was going to give it a go and

see if he could persevere through what he thought was the stomach flu. After a

quick stop at the grocery store, we headed up to Minarets Lake trailhead before

the National Forest opened up their fee booth near Minaret Vista. We parked the

cars at the backpackers parking area near the NPS Devil's Postpile kiosk. Bob

headed out early, hoping to get a good start ahead of us. He mentioned later

that he was in no mood to be sociable with the state that he was in. Romain,

Michele and myself finally hit the trail around 6:45 AM. We eventually caught

up with Bob, a couple of hours later, just

south of Minaret Lake.

Bob's stomach was still causing him trouble and it

was now affecting his lower half! Bob didn't escape harassment without a few

subtle jabs from each of us. Of course, he took it all in stride and went along

with our joking. After a quick break at Minaret Lake,

Bob and I decided to press on to Cecile Lake.

The other two took a long lunch break and enjoyed the wildflowers

that bordered the lake.

We arrived at Cecile Lake around 11:30 and recovered the plaque along with the other equipment I had stashed the week prior.

After gathering all of our equipment, we chose a

bivy site. We got the plaque ready to be packed

as Bob made the decision to press on up to South Notch

in order to leave the plaque closer to Michael Minaret. I was amazed at his

endurance. I had simply hoped he'd just be a humble fellow and take a nap at

the bivy site in order to recuperate. But Bob was off and running while I

stayed and waited for the others.

We ended up moving our bivy site

closer to South Notch after finding a campsite built by previous

climbers. By the time Romain and Michele showed up, Bob was a mere speck on the

high reaches of South Notch.

Once Bob had crossed over South Notch, he headed northwest to

Amphitheater Lake to drop the plaque off. The rest of us unpacked and casually

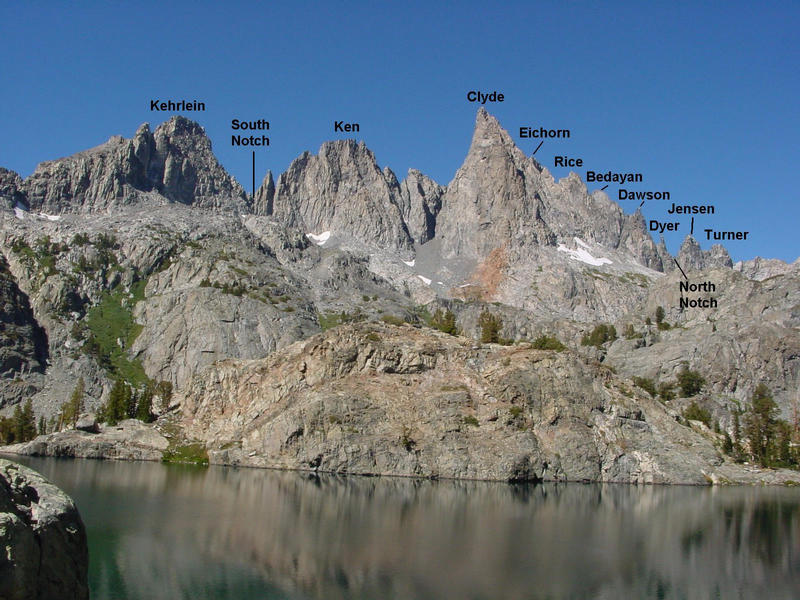

settled in. We took in the grand view that Clyde Minaret offered.

It rose up before us like a medieval broad sword, piercing

the powder blue sky. The entire Minaret range was practically in our face.

Mt Ritter and Banner Peak were directly to our northwest and they complimented

the skyline beautifully. At 6:30 PM., Bob returned to the bivy utterly spent.

He mentioned that on his return to South Notch from the west side, he had

missed the notch and passed further south to a larger notch, only to find he

was looking down upon Dead Horse Lake, just south of Kehrein Minaret. After

getting his bearings was he able to locate South Notch and descend to Cecile

Lake. We were overly glad that he had returned and had made it back in one

piece.

We turned to assessing the final plans for the approach and climb

to Michael Minaret. We knew most parties who climb Michael Minaret come in from

a cirque above Ediza Lake and then ascend North Notch, directly above Iceberg

Lake, to access the base of Michael Minaret's northwest side. Instead, our plan

was to come in from the south via South Notch, hike past Amphitheater Lake and

climb Michael Minaret's southeast side via Amphitheater Chute (I, 5.4). We

would find out later that Amphitheater Chute joins up with Eichorn Chute as it

reaches the notch between Michael Minaret and Eichorn Minaret. After ascending

Michael Minaret, we would descend either Eichorn or Michael Chutes, cross over

to North Notch and return south, above of Iceberg Lake to Cecile Lake. The plan

was settled and we started dinner and opened a bottle of Ravenswood Cab Sauvignon

to cap off the day's events. All of us took

turns keeping the evening filled with wise cracks and lively comments. Bob was

doing his best to be part of the festivities but his stomach aliment had beaten

him up good. Bob crawled into his

sleeping bag by 8:30 PM and the three of us followed suit around 9:30 PM.

Thankfully, Bob slept through the night without his upper or lower GI tract

taking turns to split him in two. Zipping up into my sleeping bag, I took a

moment to scour the glorious night sky. With the evening sky absent of any

moonlight, the stars were delivering their best show ever! Even Mars was within

reaching distance and the brightness of its red surface flirted with my eyes. I

wondered if Pete had watched a similar drama play out before his eyes as he

watched the night sky come alive above Ediza Lake some 70 years ago. What was

passing through his mind that night before his untimely death? I was sure he

felt the intimate closeness of the world around him, his beautiful Sierra

Nevada. I drifted in and out of those thoughts until the stars dimmed and I

fell peacefully asleep.

The excitement and anxiety of a new day woke me as my eyes greet the early dawn. Romain has already transitioned from cocoon to his attire for the day. I quickly follow suit and prep breakfast for the others. I spot Romain making his way down toward Bob's bivy site, headlamp ablaze. It isn't long before Bob pops up and wonders why we're all up so early, thinking we're all raving lunatics for doing so! We all figure that Bob got the much-needed rest from his gut wrenching experience the day before. A good sign indeed! Romain and I continue to prepare some reconstituted eggs and sort out the individual food allotment. Michele stirs and eventually makes her way out in time for Romain to serve Bob breakfast in bed'. We both chuckle at the gesture and make a little bet on how long Bob will hold the eggs down.

But the real delight was watching the morning daylight drench Clyde Minaret

and reveal its fluted muscles and striking

lines. What an amazing sight to see before us! By 6:30 AM, we all had breakfast

and made final preparations to ascend South Notch. We took the time to take a

few snapshots of each person before Clyde Minaret.

By 7:00 AM, Romain headed for the glacier on South Notch, with

Michele and myself ten minutes in tow. Bob made one last pit stop and was not

far behind. I could tell Bob was back in tune after he passed us both on the

talus field. We all soon rejoined at the glacier

in order to put our crampons on. Michele and I were placing on

new Grivel G12's and having a bit of trouble dealing with the excess webbing

provided. After finally securing our crampons, we were off toward the notch.

Bob reached the notch first, while Romain followed closely behind. Romain

paused at the top of the glacier to capture us on video. As we climbed to South

Notch, we enjoyed the landscape to the east.

The view of Cecile Lake and the Volcanic Ridge

was just as striking as the view to the north,

toward Ritter-Banner. The snow was icy but in great shape and we continued to

make quick progress. Bob was a third of the way up on the west ridge of Kehrein

Minaret (a 3rd class route) by the time we all reached the top of

the notch. We watched him make an attempt to go around a small gendarme to the

exposed north face. But the 4th class exposure proved too much for

openers and Bob returned to us within minutes. Once together, we headed for

Amphitheater Lake, where Bob had stashed the plaque. Bob was soon lamenting the

fact that he would soon be toting the 37-pound plaque, in addition to all his

additional gear. We all had to wonder what other requirements were needed to

make it to Michael Minaret, whose ramparts loomed before us to the northwest.

Once at Amphitheater Lake, we refilled up on water.or rather, the other three fill up on

water. This would be my self-proclaimed mistake.

I was just way too excited to make the approach into Amphitheater Chute (I, 5.4).

Again, we all took time to take photo shots.

This would be our route in order to reach The Portal' and

eventually the NW face of Michael Minaret. Romain would suffer from my mistake

as I eventually mooched H2O from him for the remainder of the day. The initial

approach up to the chute involved a quick walk across a small glacier and then

a 3rd class talus slog.

Romain commented that we should be done with the route in less than a couple of hours,

to which Bob countered that it would take at least three.

Grade I alpine routes have a way

of stretching out longer than one might imagine. Little did we know that it

would take well beyond even our closet estimation.

A quick alpine 5.4 would soon lead us into believing something else!

R.J. Secor describes in his book, High Sierra: Peaks, Passes and Trails, that there are two chockstones in the route, but we end up finding four, all of them initially visible from our first views on the approach. We find that his description and ratings are a tad bit off. The first chockstone is more like a 4th class bypass to the right and we all did so without roping up. At the base of the 2nd chockstone, we stopped to rope up as things became more serious. Nobody was particularly eager to run up on lead, and by majority consensus, I was nominated to take it on. Just by the looks of where we needed to go, it appeared beyond the realm of 5.4. The route takes on the right wall and ascends 30 feet to a right facing dihedral. From there, it appeared that a poorly protected traverse was required. I scramble the initial 10 feet before roping up, in which Bob states, he was not willing to carry an additional plaque in my behalf.

After a little morbid humor, I rope up, with Bob belaying,

and begin the climb to the dihedral.

My attention was quickly turned to the loose

condition of the route and the precarious rock strewn about it. To my left was

a football-sized rock, clinging by micro granules. All that was needed in order

to launch this thing was a slight brush of the rope as it dragged by. I warned

the others and made sure they moved far to my right as I dropped it into the

chute. The loud crash brought everyone into reality check. I finally reached

the dihedral and found the protection poor. Most of the corner flared inside

and required bigger pro. It dawned on me that a large Alien would work wonders

here but I was feeling the psychological impacts of witnessing how really loose

Michael Minaret was. I made the call to down climb, not feeling comfortable to

lead in approach shoes and a weighty pack that carried our rotor hammer drill

and materials.

I stopped at my second placement, a 3/8 Alien, and discovered that the trigger was out of reach within the crack. I made several attempts to release the trigger but came up empty handed. With no nut tool between any of us, we end up leaving it there. After I make it down to the chute, we decide to have Romain lead the section, without his pack. We would then haul his pack on a trail line, which was draped over the chockstone, once the second to last person had made it above. Romain quickly put on his rock shoes and made smooth work up to the dihedral. Once there, he was able to place a piece in the upper reaches of the dihedral and continue up to the traverse. We watched as he did it in good style and calmly crossed the ticklish traverse above the chockstone. Upon arrival, Romain established a belay and brought Michele up, from which she trailed a rope for Bob. We soon discovered the dihedral was not an easy cake walk and the traverse would get the best of us due to its bad fall potential. Simply by listening to Michele's nervous explicatives, I was convinced that I should take my follow-up seriously. Bob soon followed third and had a horrible time at the crux.

Keep in mind; Bob was carrying 50-plus pounds of equipment on

his back. All of his muscles were stretched to their limit as he struggled up

the dihedral. Several times, the plaque in his pack caught on the upper right

overhanging side of the wall, preventing him from making further progress. At

one point, it appeared that Bob was going to take a fall. It drew immediate

concern as the rope was leading over a sharp shelf above him. I just offered

words of encouragement, as Bob remained semi-composed. Panting, sweating, and

cursing (definitely not Bob's style), he eventually hauled himself over to a

ledge to the right of the traverse. I could tell his arms were cooked, in which

he took a well-deserved five minute rest. Bob would make it over to the belay

using a lower set of holds below the original traversed line. Meanwhile, Romain

had thrown a 7mm haul line down to me so we could get his pack above

the chockstone.

My only concern was that the haul line stay centered on the stone itself so the pack wouldn't drift into the corners of each side of the chute as Romain hauled it upward. I could hear Bob make his way onward and upward in the chute. The remaining terrain was very loose 3rd and 4th class, eventually leading to the final two chockstones. At the count of three, Romain and I got the pack on its way and over the top of the bus sized stone. Feeling assured that all was settle above, I prepared to tie in. I could hear Romain situating the pack and trying to settle things at his loose belay. Then suddenly, without notice, the clattering sound of shifting rock echoed down the narrow chute. What followed next was the event that all climbers fear: RRROOCCCCKKKK!!!!!!, Romain belted out. By the initial sound of things, I knew this wouldn't be just a trickle of pebbles coming over the lip of the chockstone. I quickly scrambled to the base of the chockstone and clung to it for dear life. For the next 15 seconds, a barrage of jagged rocks, some the size of brief cases, pummeled the chute. Several smaller rocks ricocheted off my helmet and left shoulder. My blood pressure took a double leap as I felt my heart thrash about in my chest cavity! I felt helpless where I was positioned. Debris fell from all crevices and there was no place to go except stay close to the bottom of the chockstone.

When the rock avalanche subsided, I found it hard to leave the spot I was depending on, as I anticipated more possible granite cascades! Eventually, I backed away and found myself curiously investigating the fresh slide the rock fall had created. The air smelled electric and alive with fine rock dust floating about. Part of me was still in shock mode while the other part was welling up with immediate anger. What the f*ck?!?!, I screamed upward, half expecting an apology. But I knew that the rock condition was no better above me than it was below me. And so I settled myself. After climbing the crux and making the sketchy traverse, it became more apparent to me how bad the chute was at the belay. Rocks were practically floating on top of other unstable rocks. No matter how subtle you moved, the rocks shifted and weighted others to slide. My nerves weren't impressed!

We scrambled the remaining way up to the final chockstone on loose 3rd and 4th class rock . Upon arrival, we discover that the two chockstones are actually positioned one on top of the other, making it more of a challenge to navigate the final section of Amphitheater Chute. So much for Secor's description! The only obvious way past these obstacles was to climb the right side of the chute wall and then traverse the gap left between the two chockstones and over to the opposite side of the chute. Again, Romain took advantage of being packless and goes to leading the short 5th class section. He soon made the traverse over to the left side of the chute via the gap between the two chockstones. Once there, Romain found he was faced with an exposed and somewhat awkward face move to gain easier ground above the final chockstone. With solid confidence, Romain pulled up and over to a ledge, which contained rap slings from a previous climbing party. We all made it to the top of the final chockstone. It was clear to us that Amphitheater Chute's rating was a bit off, even with the final face move feeling 5.7ish. We decide to give the entire route a unified backcountry rating of 5.6+.

We finally reach the

notch that joins Amphitheater Chute to Eichorn Chute, on the northwest side.

By now, its 3:30 PM. Romain and Bob are a bit worried that we are running out of time and daylight. We agree to stick with our original plan by returning via North Notch (3rd class). This would mean down climbing Michael Chute, which is adjacent to Eichorn Chute, and cross the cirque below the Michael and Eichorn Minarets over to the notch. Upon crossing over the notch, this would put us just above Iceberg Lake, slightly north of Cecile Lake and our bivy site. We knew this would narrow, if not negate, the possibility of locating the actual gravesite. By now, we made the decision to simply place the plaque and hopefully return the next day. After a quick lunch of smoked Gouda, salami and baguettes, we evaluated what we need to accomplish next. I was feeling a bit dehydrated and still finding myself dependant to Romain's water supply but still eager to get to things at hand. Feeling somewhat refreshed, we took out copies of the pictures from inside Alsup's book (pgs. 116 & 117) and compared them to the area around us.

At this point, we almost had a complete view

of the northwest face but we still had a bit of traversing to do to the

west. Knowing we were at the top of Eichorn Chute, we would need to cross over

to Michael Chute for a better view. This was easier said than done but Bob set

to scrambling the exposed 4th class section over to a buttress that

separated both chutes. From our vantage point, we could see that earlier parties

had constructed a rock cairn to identify the top of Michael's Chute and allow

climber to scale this buttress up to The Portal. The Portal is a narrow slot

window that allows views into both the northwest and southwest sides. It also

identifies the section of the route, in which it turns to the west and marks

the final stretch to the summit. But our objective that day was to simply

install the plaque and leave. Trying not to feel disappointment that we would

not investigate the burial site of Pete Starr, I turned my thoughts to reality.

Time was not on our side at this point and no one was prepared for an overnight

forced bivy. We would soon find out how unprepared we actually were.

As we all made our way over to the

buttress between Michael and Eichorn Chutes, we finally get our first real view

of the of the NW face and of the place where Pete Starr had met his fate.

All of the pictures we studied beforehand were now in full-life before us. We

were all filled with awe, once we set eyes upon it. The NW face is frightfully

exposed and the terrain is wild alpine 5th class!

Between us all, a renewed respect for Clyde and Eichorn was formed. It was these two brave

souls who ascended the NW face, in order to inter Pete's body. We felt the

amazing warmth of reverence for Pete himself. To make such a bold attempt upon

such an imposing face, solo! Simply jaw-dropping! It was decided that we'd take

a few photos of Pete's Ledge and get the plaque installed. Now, where to

install it?!?

We spent some time deciding on where

the plaque was to be placed. We wanted somewhere that would be free from rock

fall, be visible to climbers coming up from both chutes, and within full view

of Pete's Ledge. We find a flat spot of vertical rock, approximately 40 feet

above the rock cairn, and decide this is the best location for anyone to view.

We break out the drill and start the installation. It takes us almost an hour

to complete the installation but the results come out nicely.

Our only glitch is that the bottom right corner

hole is a bit off center and elevated by 1, making it impossible to install

the bolt. But with three bomber ones, we find ourselves pleased with the final product.

In addition to the plaque,

we leave a weather-proof sealed nylon box, just below the plaque. The box

contains a 3x 5 leather bound journal with pen. Each of us had made entries

that were personal in nature to a man who had left a marked impression on all

of us. The box has four Phillips head screws to secure the lid. Of course, we

leave a screwdriver along with it. Hopefully, the journal is used in years to

come. After we completed things, we take the opportunity

to photograph

and digitally record

the occasion on Romain's video cam. Even though we were excited that one of our

objectives had been met, we were all anxious to descend Michael Minaret

especially Romain.

Again, we opt for Michael's Chute.

It was now 5:00 PM, leaving us 2 1/2 hours of daylight remaining. It

was a long way down to the base from what we could see. After a bit of

scrambling, we came to the first of many chockstones we would find in the

chute. Bob found a faded 8.5 mm rope, dangling down from a stately ledge, south

of the chute. We all assume this is Clyde's Ledge, which is identified in

Secor's book. Bob is willing to use it to rappel but we out vote him on this

option and chose an established anchor 50 feet up from the ledge.

This rappel would take us back into the chute. It would take us an hour and half

to complete four more rappels,

including some serious 4th class down climbing. We were

closing in on the base of Michael Minaret when I could feel the full effects of

dehydration. We make one last short rappel

to the base and prepare for the trek out from the Minaret

cirque. It was now 6:45 PM when we exit the chute; the technical parts behind

us.

At this point, my only intention was to get to the closest water source in order to rehydrate and fill the Camel Baks. Michele and Romain changed out of their rock shoes while Bob coiled and packed the 60 meter rope. Romain packed the small rope and most of the pro, while I had the drill and other tools. Romain and Bob decide to forgo the trip down to the small lake I was headed to and instead try to reach North Notch before darkness would overtake them. Little did I know at the time that Michele and I were the only ones with headlamps. I was a tad bit surprised that either one of them didn't use Michele's before they left. By now, I was down near a small alpine lake to refill our water supply. Too desperate to refresh my dry well, I find a large water runoff, coming from the cirque slabs above. Without any regards to cool points, I immediately drown myself in the chilling mountain water, taking in huge gulps of water without a single gasp of air! I eventually fill Michele's and my Camel Bak and head off toward North Notch, just east from the base of Michael Minaret. Michele had waited for me and we joined up along the way. Bob and Romain had a 20 minute head start and were already well ahead of us.

We traverse several talus gullies along the way as we try to keep an

eyeball out for the other two. As we looked to the west, we saw the sun

slip past the horizon of the Yosemite's Clark Range.

At that point,

daylight quickly faded. As the alpenglow transitioned to darkness, we donned

our headlamps. Before the last rays of light slipped away, we were able to spot

Bob and Romain just below North Notch, or what we assumed was North Notch. We

would later find out that this was The Gap' and we had all passed North Notch

sometime earlier. After a quick 3rd class scramble, Michele and I

reach The Gap and looked to the east. Expecting to see Iceberg Lake below me, I

find that we are positioned just above a small glacier. It soon dawns on me

that we had traveled too far north and we were high above Ediza Lake. Without

much hesitation, Michele and I head down to the glacier in hopes of catching

Bob and Romain on the glacier. After securing our crampons, we head out onto

the casual sloping glacier and pick up their crampon tracks. We both yelled out

to the other two, hoping to hear some kind of reply, only to be greeted by the

hushed notes of the mountain winds. Where could they be?

We assumed, at this point, that Bob

and Romain would have to be slow and deliberate with their cross country

travel, especially with no moonlight to guide them along. A creeping fear

started to build up inside me for them. I knew the terrain below the lower

section of the glacier dropped off down through steep

terraces and gullies.

One false step and it would be lights out for anyone.

Half way across the glacier, we picked up a solid trail of crampon tracks and continued to track them until the glacier ended at an alluvial fan of talus. We assumed they continue travel in the direction they were already headed. But as we press onward through the talus, it became apparently steeper and the option for downward progress became obviously dangerous. By now, the wind was picking up and the wind chill fact was kicking in. My best guess was the evening temps were already dipping into the high 20's. We explored several options to descend but ran into several dead-end, only to have the light from my headlamp pierce the inky voids below. Occasionally, we would call out to Bob and Romain but got nothing in return. My next concern came when I realized we didn't have the tech wear possible to prepare for a forced bivy. This became completely apparent when I saw Michele huddled in a ball with only light weight climbing pants, a thin poly-pro top and a light windbreaker. Our choices were narrowing and decisions needed to be made. It was only when I saw the masked expression of fear upon Michele's face was the call made to bivy somewhere in the talus field. Michele reinforced that decision by expressing her concerns. One of which was the impending possibility of hypothermia.

We were both in no shape to continue our descent. I was slowly recovering from dehydration and Michele was flat exhausted. Our only solace, in our hour of need, was that I had remembered to bring a down jacket. This would prove to be our one saving grace. I couldn't help but to think how Bob had only layered himself in thin cotton climbing pants and shirt. What was their situation and what would they do? How were they coping? Had they made it to Iceberg, in their hopes to press on the remaining length to Cecile Lake? It wasn't soon after that Michele spotted an opening to a rather large cave below some huge boulders. We emptied a few things from the pack to eliminate excess gear inside the cave. Once inside, we found that the cave spread out toward the back and the bottom was somewhat level. We tried to settle in and prepare to wait out the sapping coldness of the night. We both used our packs as head rests and insulators from the cold rock floor. Unfortunately for me, I discover that my Camel Bak had leaked along the way and everything in the bottom was soaked! The amazing thing was that my down jacket had remained dry, which would be our cherished token item for the entire bivy.

Within the hour, it became apparent to me that Michele was becoming hypothermic. The only thing she had to protect her from the bitter elements was a pair of synthetic climbing tights and a technical windbreaker. She was starting to shiver and I grew concerned about how we would hold up during the next nine hours. I gladly gave my down jacket to her and we decided to close in tight to conserve body heat. It wasn't long before we both felt the warmth generate and give us a degree of comfort. We both made light of the situation and tried to put our minds elsewhere. Michele even conjured up images of soaking in a hot bathtub while I simply tried to close in tighter. Our only discomfort was that our legs were exposed to the cold. By the 2:00 AM, we were both complaining about how we couldn't feel our legs. Our only solution was to rub our legs and intertwine them for more heat exchange. Sleep was minimal but we managed to pass our time by either trying to guess the time or simply make adjustments to our uncomfortable surroundings. Of course, the cold rock underneath us offered no solace. It simply came down to a waiting game for the sun to rise and get a fresh start once morning arrived. Occasionally, I wondered if Bob and Romain had made it to the campsite or were they in the same predicament as Michele and I. I did my best to get as much sleep between thoughts and attempted to provide Michele some comfort by shifting into a position where she was less exposed to the rock floor. Hour by hour, we did our best to overcome this little epic.

By 6:00 AM, the early

morning light sifted through the cave entrance and gave us assurance that

we'd endured our little test. We were coveting the hopes that the morning

sky would produce filtered warmth from the sun. We would soon find out as

we emerge from the talus field.

Michel

and I gathered up the extras and prepared to set out for Cecile Lake. Upon

setting our sights to the southeast, I noticed heavy clouds begin to build up

over Ritter-Banner. Their appearance was less inviting and soon produced the

occasional rumble of thunder. I scan the upper terraces below the Minarets,

hoping to spot Romain or Bob on their way to the campsite. It was certain to me

that they had also endured a frigid night as well. I couldn't help but conclude

that no one would be able to safely navigate through 3rd class

terrain without a solid light source. Michele and I made our way down to a

cirque just below the terraces we were on. This cirque is situated just above

Ediza Lake. By dropping below to this cirque, it enabled us to quickly hike

over to Iceberg Lake, which was directly south of us. By the time we were half

way down a series of 3rd class terraces,

the sky let loose on us with sleet and cold drizzle. It made all the grassy

slopes slick and muddy. My approach shoes offered hardly any traction and many

times did I find myself on hindquarters, wet and cold! We eventually broke out

onto the cirque and quickly headed south to a gap just north of Iceberg Lake.

Then came a familiar sound but one usually foreign to the backcountry. the rhythmic beat of rotor blades! Somewhere, a helo was in close vicinity. Michele and I looked at each other with a degree of disbelief, thinking that maybe Bob and Romain had called SAR with Romain's cell phone. But the thought wasn't full blown because we felt that it would be way to soon to report us overdue. For the next 5 minutes, we scanned the skyline for evidence of the helo's presence. Then, out of the low clouds near Ritter-Banner, appeared a SAR helo heading our direction. We continued to watch as the helo traveled more toward our location. I prepared to take my jacket off and give the pilot a wave, thinking that they were looking for us. Then, in the same moment, the helo headed toward the west and back into the cloud mass, by Ritter-Banner. Questions poured through my head as to what they were doing. Were they looking for us? Were they training? Was there another party in trouble?

Not too long after pondering these questions, the answer was revealed.

It appeared they were attempting a rescue

of another party who had been up on Ritter-Banner the night before. We would

find out later that a member of that team took a tumble

down the upper section of the Ritter-Banner saddle. We broke from

our interest in the helo and pushed toward the gap by Iceberg Lake. Once there,

we scoped out options for a descent into the deep crater that cradled

Iceberg, well below the Minarets.

We both spotted a faint trail that circumnavigated the

eastern side of Iceberg's talus field. By the looks of the talus field, it

appeared that a fresh slide had occurred recently and it didn't give us the

warm and fuzzy to safely travel through. After some rapid debating, we settled

on dropping down to Ediza Lake and traveled on established trails around the

Volcanic Range. Our only shortcoming. we were without a topo! I had assumed

that the trail from Ediza would lead us to the John Muir Trail, which would

head south to the Minarets Lake Trail. Later, I would discover, through the aid

of a fisherman, that we had some substantial traveling to cover.

As we passed Ediza Lake, we noticed

a group of Mono County SAR members coming up the trail. Inquisitively, we

inquired about what was happening up near Ritter-Banner. They mentioned that

another party was in need of assistance. Whew! That was a rest off of my mind,

knowing we weren't their objective. Little did we know that Romain and Bob

would be calling the same SAR crew

via Romain's cell phone through their dispatch. an hour later!

Clueless as we were, we continue down past to Shadow Lake and headed south on the JMT, in hopes of reaching the Minaret Lakes Trail. By the time we reached the ridgeline above, our focus turned to some cat napping. Having gone through the night with absolutely zero sleep, we took advantage of the occasional sunrays that poked through the overcast sky. We were both feeling the fatigue but I knew we needed to reach Bob and Romain before they would make their own call to Mono County SAR. We headed up the trail toward an unfamiliar lake. There, I spotted a fisherman and asked him what lake we were at. Rosenberg Lake, he replied. Huh?? I had assumed we were close to the Minaret Falls area. I asked if he had a topo, which he produced for me to look at. Upon locating the lake, I was shocked with surprise that we had more mileage ahead. A LOT MORE!!

When I mentioned this to Michele, I could see concern, fatigue, disappointment and a degree of despair settle on her face. We had discussed other options and came to an agreement that we'd hike to the trailhead. From there, we'd head into Mammoth and call Romain on his cell phone. Secretly, we both looked forward to civilized food and hot showers. Within a few hours, we had reached the trailhead and were back at the cars. I noticed a small business card had been placed upon Michele's windshield. The Mono Country SAR had left us a note stating that we were considered missing persons and to contact them if we returned. We hopped into the truck and headed up to Mammoth. We made a quick phone call to the sheriff's office. They were glad we had turned up safe and sound. In return, we thanked them for their efforts and overall concern. They said they would pass on the information to the SAR team and ensured us that the county sheriff would be informed as well.

By now, it was 4:00 PM and we knew our companions were anxious of our whereabouts. After checking into the Rodeway Inn at Mammoth, we attempted to call Romain but found we only had his home number. After leaving a message at his home, we hoped his wife would return the call and provide his number. We waited. I wondered where he and Bob were and if they were safe as well. About an hour later, the phone rang and it was Romain! I assumed he was calling us from Cecile Lake and letting know they were fine. We told him that we were in good health and in Mammoth. I assured him that we contacted Mono County SAR and also informed them of our safe return. To my surprise, he told me that he and Bob had packed up most of the campsite and hiked out. They too were in Mammoth and preparing to check into a motel. Which one? I replied. The Rodeway Inn, he quickly stated. I told him we were in the same motel down at room 118. As if fate were playing a prank, Romain told me they got the room right next to ours. Within minutes, Bob and Romain showed up. All of us elated that we all were in one piece. We all shared accounts of our mini-epic, piecing together all the missing segments along the way. We had completed what we came to do and we all sensed fulfillment in doing so.

The very next day, Michele and I headed back up to Cecile Lake to retrieve our gear, while Bob and Romain parted ways with us. As I took one remaining look toward the Range Of Light that day, I reflected on the immense impact the experience had left us. How we each were unified in honoring the spirit of climbing and were able to pay our respects to a man so devoted to the future of mountaineering. Pete Starr not only left his legacy but his profound love for the mountains, allowing each of us to share in the grand adventure of mountaineering and to experience the freedom of the hills'. For his complete devotion, Pete Starr will never be forgotten. His memory will always live in the heart and soul of inspiring climbers throughout the world. today, tomorrow and forever!